Cogita is Scary When She Speaks in Classical Chinese

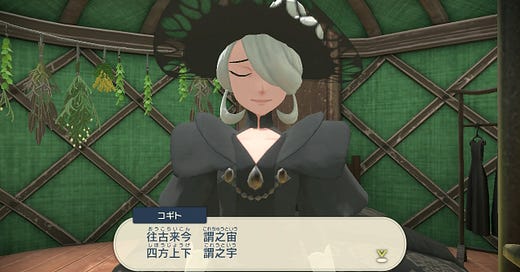

I recently subjected myself to a Japanese-language playthrough of Pokemon Legends: Arceus. In the whole playthrough, there was one moment that sent me into a panic and left me shaken. That moment came during my first meeting with Cogita, when in the midst of a perfectly normal Japanese-language conversation she drops a sentence that is, at first glance, completely incomprehensible.

The sentence she speaks is this:

往古来今 謂之宙、

四方上下 謂之宇

The version of this text given in the English-language PLA is simple: "the expanse from antiquity to eternity and the expanse to all sides, above and below". But in Japanese, this section throws the player into a different linguistic register altogether. I stared at the console for a moment and put the game to sleep, then set my Switch down on the desk and stared into space. My blood froze and a chill gripped my heart. “Was that freaking kanbun?” I thought. And then, “If she dumps a bunch of lore in kanbun I will never manage to get to the end of this game.”

Fortunately, she switches back to normal Japanese immediately and I was able to read again. But I want to take a moment to explain how this scene works for a player, why and how I was actually wrong, and what it all indicates about Cogita.

Kanbun is a method of annotating Chinese texts to read their characters (kanji) according to Japanese grammar. It has been used since the Nara period—so sometime between 710 to 794— and was the main language of scholarship, law, and religious study for many centuries. Kanbun often looks quite a bit like this:

(Image from “Kanbun” on Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia https://alchetron.com/Kanbun)

You can see the large Chinese characters and then the little marks to the left and right that indicate in what order to read the characters-- whether to go forward, stop, jump back, jump back further, etc-- so that the text makes sense in Japanese. The annotations also include several pronunciations that are alternatives to the Chinese. Even with all of this explanation, it is still pretty hard to read.

Fortunately, the player can start to grasp the meaning of the sentence after a few seconds of staring. The kanji to the left are at a low enough grade level that it’s easy to take them in quickly and guess at the meaning (literally “before, past, future, present,” and then below that, “four directions, up, down”). The kanji to the right, which are not easy to read, have furigana that explain “are called time,” and then below, “are called space.” And then suddenly you can loosely understand the kanji altogether, feeling your brain rearrange itself in comprehension while breaking every grammatical rule of modern Japanese. It’s a very strange feeling, and it’s a fun trick for such incomprehensible ancient phrasing to suddenly make sense to a modern player.

I initially thought this text was in kanbun. The reason that this was such an appealing initial interpretation of Cogita’s line is that one, it would suggest that Celestican culture had roots as far back potentially as 710 CE. And two, that would very loosely connect Celestican culture with the Heian period, a kind of golden era for Japanese culture that lasted from 794 to 1185 CE. Cogita, with her knowledge of myth and legend, familiarity with kanbun and thus Chinese texts, and apparent skill with poetry (it’s theorized she wrote the ancient verses), has skills that are directly in line with some of the most learned women authors of the Heian period. And these abilities represent a different, archaic concept of leaning and knowledge that dates from that period.

But I googled the phrase that Cogita speaks and realized that this theory was totally wrong. She’s even more intimidating and, potentially, much older.

Cogita does not speak kanbun here. She speaks pure, unmodernized, untranslated ancient Chinese. Specifically she’s quoting a passage from the Huainanzi, a mostly Daoist text on rituals that dates from 139 BCE. Who goes around quoting unfiltered ancient Chinese? Cogita, that’s who. And with no warning. I hope you see where her descendant gets it from. At least buy me a drink first, geez.

This potentially re-dates Cogita, and we might think of her as either being two millennia old or as descending from the midst of a culture roughly that age. This reference to the Huainanzi and its link to Taoism also gives her the image of a reclusive scholar, who retreated from society to dedicate themselves to study and contemplation. Importantly, in Daoist texts some reclusive scholars are immortal, reinforcing a popular theory about Cogita. Her open disdain for Volo, a skilled merchant with strong (metaphysical) ambitions, might place her as one of the more recent versions of the scholar-recluse. Beginning in roughly the 1600s, this more recent concept of literati scholars left society in rejection of corrupt politics and a merchant class yearning to join their intellectual ranks. Her attitude, and the fact that she lives away from society in her “Ancient Retreat,” seem to conform to this image. Additionally, her refusal of the term “mistress” and the suffix “-sama” in Japanese might refer to this rejection of her position and status in society.

(Here's a bit more on the topic: https://asiasociety.org/new-york/exhibitions/artful-recluse-painting-poetry-and-politics-17th-century-china)

So what does Cogita say in ancient Chinese?

“From furthest antiquity to the present days is called ‘extension-in-time’;

The four directions [plus] up and down are called ‘extension-in-space.’”

Not too far off from the English version! This is part of an explanation Cogita gives after you ask which Sinnoh is real, the Diamond Clan’s or the Pearl Clan’s:

“The expanse from antiquity to eternity and the expanse to all sides, above and below…time traces the path we tread from the here and now into the future…While space yawns all-encompassingly, surrounding us in every direction. You see, don’t you? The two together, time and space, comprise all creation—the universe. How can one claim that either is greater than the other, as those two clans do?”

Cogita here gestures to the equal status of time and space, and point out their mutual dependence in making up all of creation. She seems to indicate an understanding of a higher order, Arceus, that transcends the duality of Dialga and Palkia. But her understanding draws heavily on Daoism. Here is the quote in context, as selections from the full chapter that she cites in the Huainanzi:

“The ultimate greatness of the Uncarved Block (the mind) is its being without form or shape;

the ultimate subtlety of the Way is its being without model or measure.

From furthest antiquity to the present days is called ‘extension-in-time’;

The four directions [plus] up and down are called ‘extension-in-space.’

The Way is within their midst, and none can know its location.

Of old,

Feng Yi attained the Way and thus became immersed in the Great River,

Qin Fu attained the Way and thus lodged on Kunlun.

Through it [i.e., the Way],

Bian Que cured illness,

Zaofu drove horses,

Yi shot [arrows],

Chui worked as a carpenter.

What each did was different, yet what they took as the Way was one.

Now those who penetrate things by embodying the Way have no

basis on which to reject one another. It is like those who band together to

irrigate a field—each receives an equal share of water.

Now if one slaughters an ox and cooks its meat, some will be tart,

some will be sweet. Frying, stewing, singeing and roasting, there are

myriad ways to adjust the flavor, but it is at base the body of a single ox.

Chopping down a cedar or camphor [tree] and carving and splitting it,

some [of it] will become coffins or linings, [and] some [of it] will become

pillars and beams. Cutting with or against the grain, its uses are myriad,

but it all is the material from a single tree.

Thus, the designations and prescriptions of the words of the Hundred

Traditions are mutually opposed, but they cleave to the Way as a single

body.”

Cogita’s reference to Daoism specifically rejects the false opposition of aspects of reality. This philosophy advances a non-dualistic vision of the divine, recognizing only the whole of existence and rejecting the false opposition and division of its parts. Daoism’s commitment to the idea of a synthetic whole that transcends duality was also frequently used to illustrate Buddhist principles, especially its rejection of false conceptual oppositions (I wrote a bit about this in Part 1 of the series). This background lends massive philosophical weight to criticize the opposition and conflict between the clans and note that this turns their attention away from the true divine—in Daoism, the Way, and in PLA, Arceus. This philosophical explanation also helps point us to how we might understand Arceus.

Rather than a singular, controlling entity, we can see Arceus as the actual whole of existence, the synthesis of time, space, and chaos. This reference aligns both Cogita and Arceus with a very specific Daoist philosophical position, and with a detached attitude towards human society and its flawed oppositional camps. And notably, it puts Celestican culture in the context of a philosophy that is over two millennia old.

This essay was initially posted by the author on Archive of Our Own. It remains cross-posted there.

The Kanbun image is taken from the following site, which also has a much more thorough explanation:

Here is a link to the Chinese text of the relevant chapter of the Huainanzi: https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=gb&id=3206

All English Huainanzi translations are from: Liu, An, and John S. Major. 2010. The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China. New York: Columbia University Press. Link.